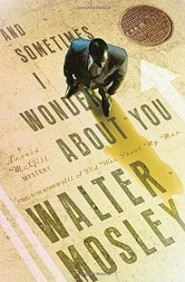

Author Walter Mosley in front of his childhood home in the LA neighborhood of Watts. He’s standing with his father.

In this season of anger in many black communities that are reacting to police brutality, we’re remembering the largest urban riot of the civil rights era.

Fifty years ago this week in Los Angeles, the African-American neighborhood of Watts exploded after a young black man was arrested for drunken driving. His mother scuffled with officers and was also arrested, all of which drew an increasingly hostile crowd.

Novelist Walter Mosley was a boy at the time, growing up in Watts. He says of that time, “It’s a hot summer day, you know, in 1965 … and people are fed up with the last 500 years of oppression, and so there was a riot. You couldn’t have predicted it. It was just people said, ‘OK, today, I’ve had enough.’ ”

He shared his memories of the riots on Morning Edition. These highlights include some of the on-air interview, and some excerpts that did not air.

Interview Highlights

Remembering the first night of riots

When I was a kid — I was 12 years old — I belonged to an organization called the Afro-American Traveling Actors Association, and we did civil rights plays. The main night of that riot, the apex of the riot, we went down to the little theater on Santa Barbara — now called Martin Luther King — to do our play. But nobody came, because people were rioting. Either they were rioting, or they were in their houses, hiding from rioting. And we had to drive out, and driving out, we drove through the riots. It was an amazing sight.

And when I got home, my father was sitting in a chair in the living room — which he never did — drinking vodka and just staring. And I said, “Dad, what’s wrong?” He says, “You know, Walter, I want to be out there. I want to be out there, rioting and shooting. But I know it’s wrong. I want to do it, but I can’t do it.” And he was just … it tore him up, the emotions it brought out in him.

On his father’s reaction

I don’t think there was a black man or woman in America who didn’t understand why it was happening. Most people didn’t riot, of course. … But everybody understood the anger and the rage, that the police could clamp down on you at any moment. It doesn’t matter if you’re innocent or guilty. What matters is, if you were a white guy over in Beverly Hills, they wouldn’t be clamping down on you like that; they wouldn’t respond to you like that.

It’s the same thing that happens today; it’s just that we have social media. So, you know, a woman gets killed in Texas, and we say, “Well, why was she arrested?”; “Why was she in jail?”; “How did she die?” These are questions only people in the black community asked a long time ago, because we knew it, but nobody else knew it, because nobody covered it. … And, I want to add, as much as black people understood it, the white community was completely ignorant of anything going on in the black community. And it was such a shock, it scared them for the next five years.

On whether the riots scared him personally

I was scared, you know, because, No. 1, it was an interracial group. So there were a couple of white people in the car, and they were like, on the floor. And then you would see things, you know, people jumping out of windows. They were looting. I saw one guy just lying out on the street. I don’t know what happened to him. The police were driving by, four deep in the car with their shotguns held up, but they weren’t shooting. They were just passing through. You could feel the rage. You could feel that civilization at that moment was in tatters. I was nervous, but I didn’t know enough to be really, really scared. Which was lucky for me.

On how the unrest affected the neighborhood

It hurt the community in some way. But, you know, when all the stores in your community are owned by white people, and you burn down those stores, even though you’re hurt in a way, you’ve made a statement. Those people paved the way for a lot of change in the rest of America. And so, whatever was lost, I believe a lot more was gained. Because it was just expressing that anger. You’d ask, “Well, how many black people feel like this?” And, well, 99 percent of them feel like this, and another 1 percent are really mad. That would be the answer.

(via NPR.org)

Nothing says summer like curling up on the porch or the beach like a good read. There are plenty of new books by black authors, and great ones you might have missed. Just find yourself a cozy place, in the homestretch of summer to settle in and dip into the reading stash. What are you reading and loving this summer?

Nothing says summer like curling up on the porch or the beach like a good read. There are plenty of new books by black authors, and great ones you might have missed. Just find yourself a cozy place, in the homestretch of summer to settle in and dip into the reading stash. What are you reading and loving this summer?