by Walter Mosley

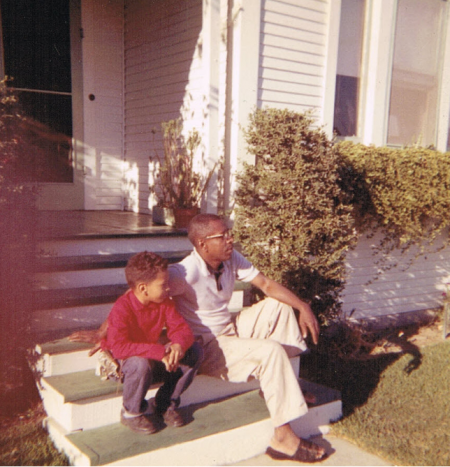

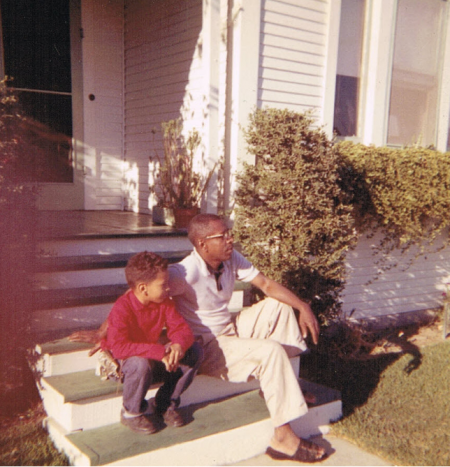

Two thousand sixteen marks the 100-year anniversary of my father, Leroy Mosley’s, birth. He was and is my inspiration, the man who taught me to bob and weave in life and art. I came into being shaped by the stories about his childhood in Louisiana and the grinding poverty he endured there, the bloodletting and laughter in the Fifth Ward in Houston and the harsh enlightenment he received in the Army.

My father was born in the middle of one world war and served in the next, but his true battles, like those of so many African-Americans, were fought closer to home. Rural life in southern Louisiana was a threnody of destitution and racial oppression. But Leroy and his two half sisters were protected and fed by family that loved them and strangers who understood their pain. In the Old South, subjugation brought out the generosity in many of those persecuted, and black folk were masters of making something from nothing, be it that day’s jambalaya or a suit of clothes stitched together from rags.

Leroy named me for a ghost, a fiction — after his father, who had committed a mysterious and terrible crime back in Tennessee and went by the alias Walter Mosley. Walter was a logger and would leave for weeks at a time, working on crews hewing trees and floating them downriver to New Orleans. The boy was close to his mother, the fount of warmth in the home. She died when he was only 7, and shortly after, Walter went to work one day and never returned. Leroy’s half sisters were shuffled off to their blood mother’s relatives, and he was left to live with cousins who mistreated him. At 8 years old he jumped a freight train headed for Houston, where his mother’s father was purported to live.

The two didn’t get along. Leroy was permitted to sleep on the porch, but he had to find his own food and money. He grew up quickly in the Fifth Ward, learning to carry two guns and one razor at all times. He could fight hard and run fast, cook and sew, clean, do carpentry and fix any engine. He learned to type and write, and he was a masterful storyteller. But that’s not unusual for poor people living under the thumb of history: My Jewish relatives from Eastern Europe were no different; they’d sit up all night regaling one another with the horrors they had survived.

It was Leroy’s dream to write for the popular pulp magazines. He even sent a cowboy story to a magazine — only to see it published a year later, under someone else’s name. He gave up. It was not possible, he concluded, for an impoverished black man in the Deep South to become a writer at that time. It’s hardly easier now.

But it took World War II for my father to truly quit the South. When he realized that more of his draft-age friends had died back in Houston than in the war, he headed for Los Angeles. There, he met and married my mother and became a fiercely loving father who prepared our every meal. When I was 13, I asked him what he wanted me to be when I grew up. He said he wanted me to do whatever I wanted, that he had no directive. I took his lessons from poverty and decided to become an artist — someone who makes something from nothing. I decided to make something from the stuff of his stories, of pedestrian, tragic life, like the time he decided to eat at an all-white cafe in the late 1940s. Making it as far as the counter, he ordered a tuna melt. “That sandwich tasted like freedom,” he told me. But suddenly the white man sitting next to him dropped dead. “I realized right then and there that, freedom aside, no man, no matter who he is, can escape his death.”

My father’s life intersected with a century of conflict, horror and invention. He deciphered these histories for me, making me his scribe in a new century. My successes were his successes, and his stories thrum in every word I write. He taught me to see like a writer, to be attentive to the stories that spring up everywhere: the epileptic guy on the corner medicating his condition with wine; the man lamenting his cheating wife; a woman passing by, sheltering a child in her arms; to say nothing of his own tales — Leroy came to own three apartment buildings, but his tenants assumed he was the handyman. It’s an attentiveness to the world, to ordinary suffering, to the love that persists in its midst. My sense of the world, of history and humanity flows from this awareness — and the attendant grim humor — my father used as his guiding lamp in the darkness cast by racism and poverty.

He was riddled with cancer the last few times I saw him. On one such day, my mother and I were leaving the house in her car. My father, who we were told was too sick to stand, had somehow made it to the back porch. As we drove off, I saw him leaning heavily against the banister. But when we made eye contact, he suddenly smiled and lifted his hand. This was his gift to me: an indomitable spirit and the talent of taking the beauty and refusing the rest.

Walter Mosley is the author of more than 50 books, including the Easy Rawlins mystery series, and the recipient of PEN America’s Lifetime Achievement Award. His most recent novel, “Charcoal Joe,” was just published.

A version of this article appears in print on June 19, 2016, on page BR25 of the Sunday Book Review with the headline: Finishing His Sentences.

Veteran storyteller Walter Mosley is back with another installment in the life and times of Easy Rawlins in Charcoal Joe. This is terrific news on several fronts: Easy is one of the finest characters in modern-day suspense fiction, complex and artfully drawn; the heroes and villains change sides with some regularity, including the main character; and the story offers more than its share of twists and turns to confound the reader. The titular Charcoal Joe is something of a legend in the circles of Los Angeles bad guys. Easy has stayed outside Joe’s sphere, but all that changes when he is tapped by his longtime frenemy Mouse to look into the murder charges against a young friend of Joe. Violence raises its ugly head, and our hero must take some serious evasive action to protect the lives of his family and loved ones. The Easy Rawlins saga has followed the landlord-turned-detective from the early post-World War II years through the Jim Crow 1950s and up to 1968 in this latest installment. The late ’60s were tumultuous times in Southern California, and Mosley deftly weaves social commentary into the narrative.

Veteran storyteller Walter Mosley is back with another installment in the life and times of Easy Rawlins in Charcoal Joe. This is terrific news on several fronts: Easy is one of the finest characters in modern-day suspense fiction, complex and artfully drawn; the heroes and villains change sides with some regularity, including the main character; and the story offers more than its share of twists and turns to confound the reader. The titular Charcoal Joe is something of a legend in the circles of Los Angeles bad guys. Easy has stayed outside Joe’s sphere, but all that changes when he is tapped by his longtime frenemy Mouse to look into the murder charges against a young friend of Joe. Violence raises its ugly head, and our hero must take some serious evasive action to protect the lives of his family and loved ones. The Easy Rawlins saga has followed the landlord-turned-detective from the early post-World War II years through the Jim Crow 1950s and up to 1968 in this latest installment. The late ’60s were tumultuous times in Southern California, and Mosley deftly weaves social commentary into the narrative.